At the age of four, Keith Haring learned to draw from his father, who would amuse him by creating cartoon animals. Although his father never pursued an artistic career, he encouraged Haring to continue drawing throughout his school years. Drawing became a means for Haring to earn respect and communicate with others. By the time Haring was eighteen, his primarily cartoon-focused work began to shift towards abstraction and spontaneous action. He developed an interest in Eastern calligraphy and the art of gestural drawing.

When Haring moved to New York City at twenty, he started using his art to raise awareness and spur action on causes he supported. One notable example is his Fertility series, a collection of five screen prints created in 1983 addressing the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Through these vibrant prints, Haring used his drawing and color skills to highlight a complex issue often overshadowed by stigma and neglect. The series' bold colors and powerful imagery reframed the HIV crisis, cementing Haring's status as both an artist and a social activist.

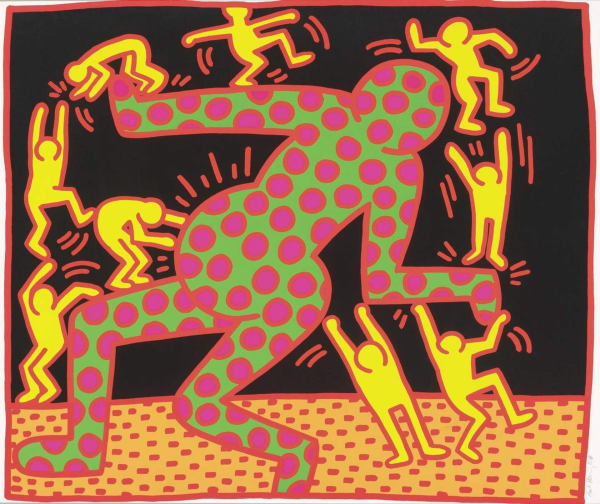

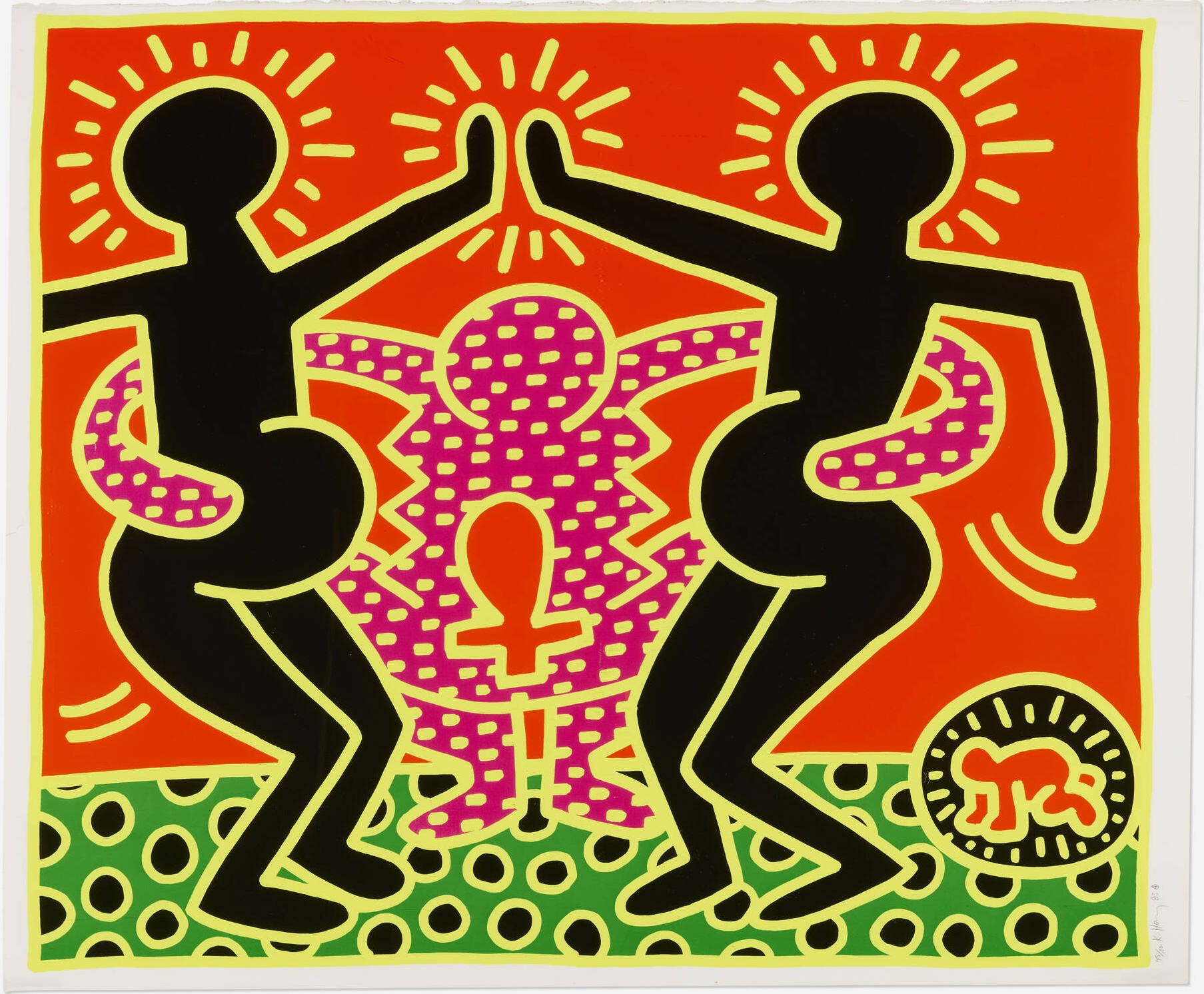

In the Fertility series, Haring reinterprets his iconic matchstick figures, usually faceless, each with a pronounced pregnant belly. These figures engage in prayer and dance, creating a sense of ritualistic significance.

In the first print, four women reach towards a floating baby, known as Haring's radiant baby—a symbol of pure, positive human existence. Here, the baby, marred by green spots symbolizing HIV, represents the threat of disease transmission during pregnancy.

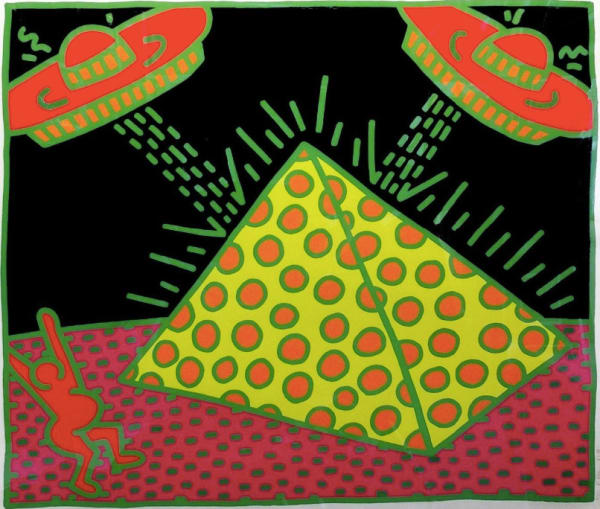

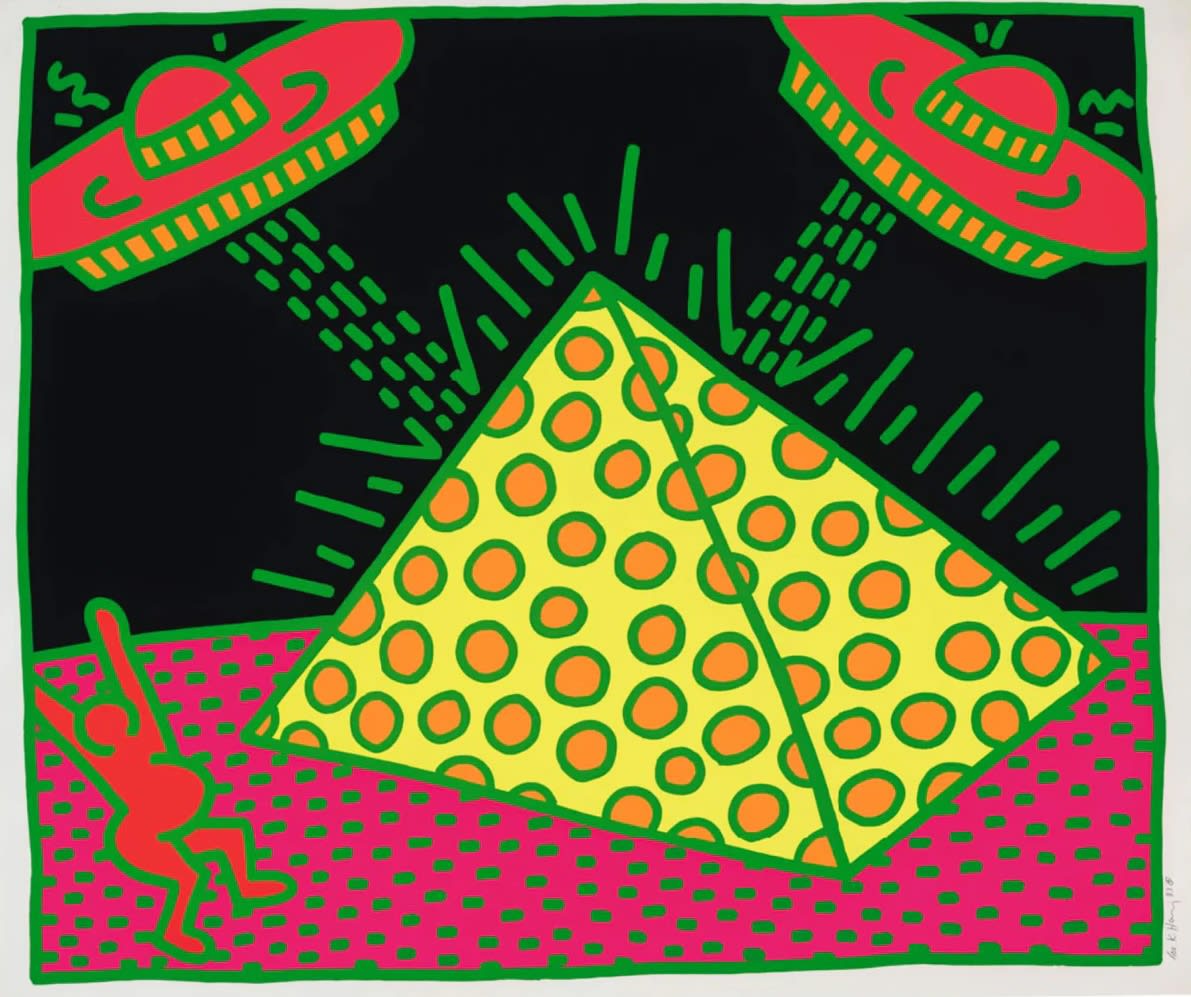

The second print features another Haring hallmark—the UFO. Two spacecraft hover above a pyramid marked with green spots. A pregnant woman stands below, arms raised in supplication, blending the ancient with the otherworldly. The narrative suggests her plea for guidance and salvation from an alien power, enhanced by the ominous black, yellow, and pink panels.

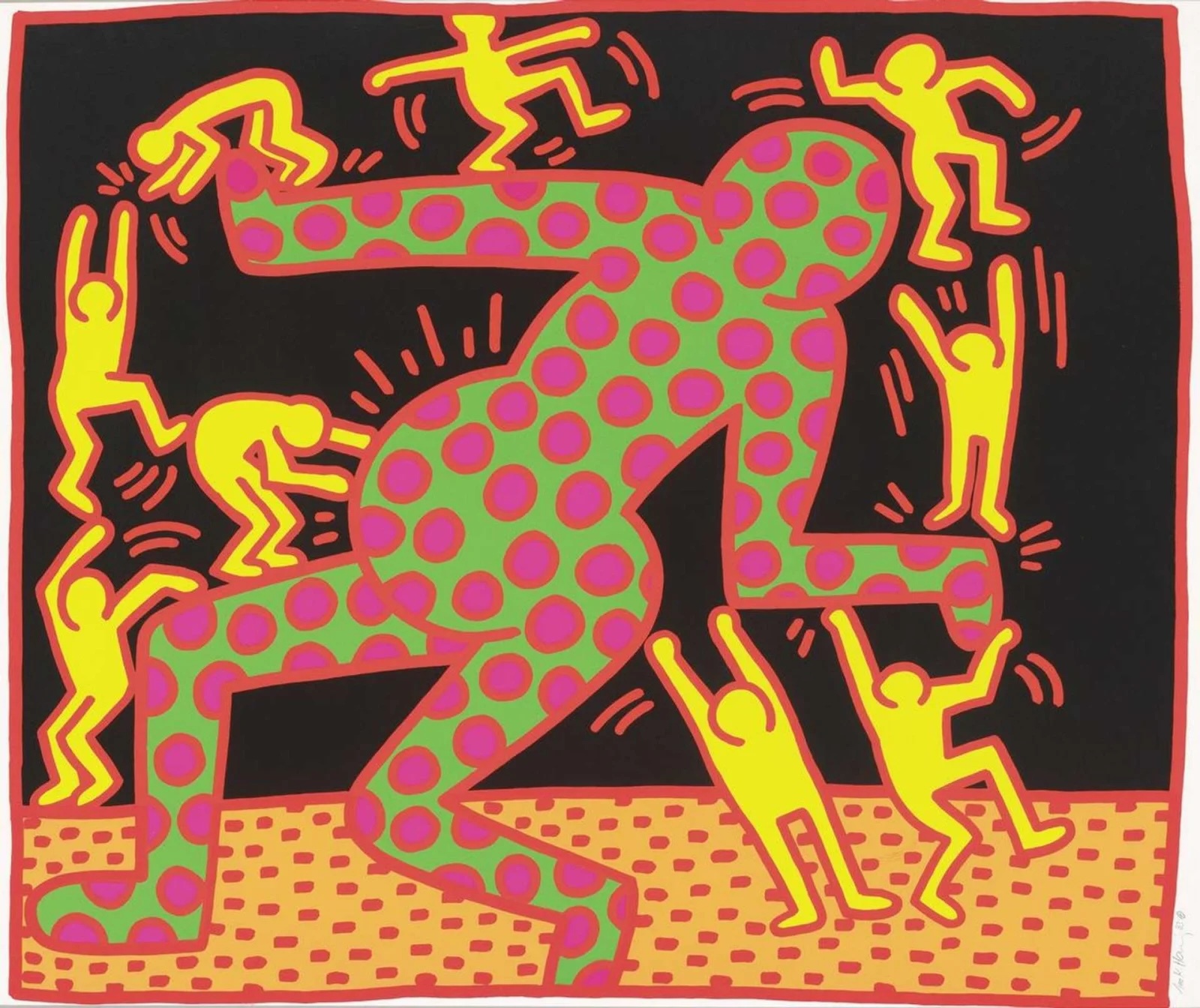

Throughout the three remaining prints, Haring's matchstick figures appear as colossal, god-like beings, symbolizing fertility deities or the disease itself.

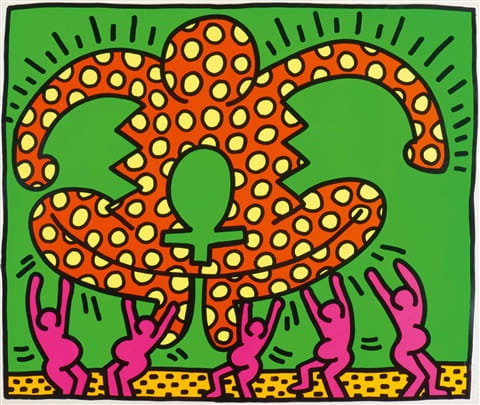

In the fourth print, two pregnant women with touching palms are embraced by a central figure with an ankh-shaped abdomen, which reappears in the fifth print.

This ankh, an Egyptian symbol of life, underscores the strength and resilience of African women facing adversity. By using universal symbols like the pyramid and UFO, Haring emphasizes the empowerment and cultural heritage of these women.

The Fertility series oscillates between celebration and foreboding, reflecting the complex emotions surrounding the HIV epidemic. Haring’s use of neon colors counteracts the dark subject matter, infusing the artwork with vibrancy and life. Most importantly, Haring gives Sub-Saharan women a life-affirming narrative and much-needed representation, portraying them as part of a vibrant community with a rich history, not defined solely by the disease.

Five years after creating the Fertility series, Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. This personal battle drove him to become an advocate for AIDS awareness, challenging societal taboos. While AIDS discussions at the time often focused on homosexuality, the Fertility series highlights Haring's activism on a global scale. Tragically, young women in Sub-Saharan Africa still face high risks from AIDS during pregnancy, making the series relevant today.

Keith Haring's Fertility series exemplifies the power of art for social change. Through these iconic prints, Haring not only addressed a global crisis but also celebrated the resilience of African women, bringing crucial attention to their plight. The series stands as a powerful reminder of art's enduring impact in raising awareness and advocating for societal change.